Horace Pippin. Supper Time (detail), c. 1940. Oil on burnt-wood panel. BF985. Public Domain.

Digging Deeper into Horace Pippins’s Supper Time

Libby Kandel, Graduate Research Intern

Fall/Winter 2022

Though Dr. Albert Barnes famously collected European modernist painters, he was also an avid supporter of artists closer to home. Room 12 of the Barnes collection, also known as the American Room, features ensembles that showcase Dr. Barnes’s love and support of contemporary American art. Included in Room 12 is Supper Time, a small painting of a family enjoying a meal together on a snowy winter night. It is one of three paintings by the artist Horace Pippin hanging in the gallery and has recently been the subject of a Barnes research project.

The east wall of Room 12. The paintings in the same row as Supper Time are (from left) Giving Thanks and Christ and the Woman of Samaria, also by Horace Pippin. In the bottom row, paintings by Maurice Brazil Prendergast and Ernest Lawson flank a work by Jules Pascin.

Who Was Horace Pippin?

Horace Pippin was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, in 1888. He had no formal art education or training but began drawing and experimenting with crayons as a small child.¹ Toward the end of his life, he described his artistry as a “talent that [God] has given me from birth.”² In his twenties, Pippin enlisted in World War I, fighting in the 369th Regiment—also known as the “Harlem Hellfighters,” one of the first army units predominantly made up of men of color.³ During his recovery from an injury to his dominant arm in combat, Pippin began drawing on cigar boxes with charcoal as a means to engage with what he described as “the things that [he] had always loved to do.”⁴ This practice led to a greater interest in pyrography, also known as pokerwork or wood burning, in which Pippin would use a heated tool to incise marks into a wood panel.⁵

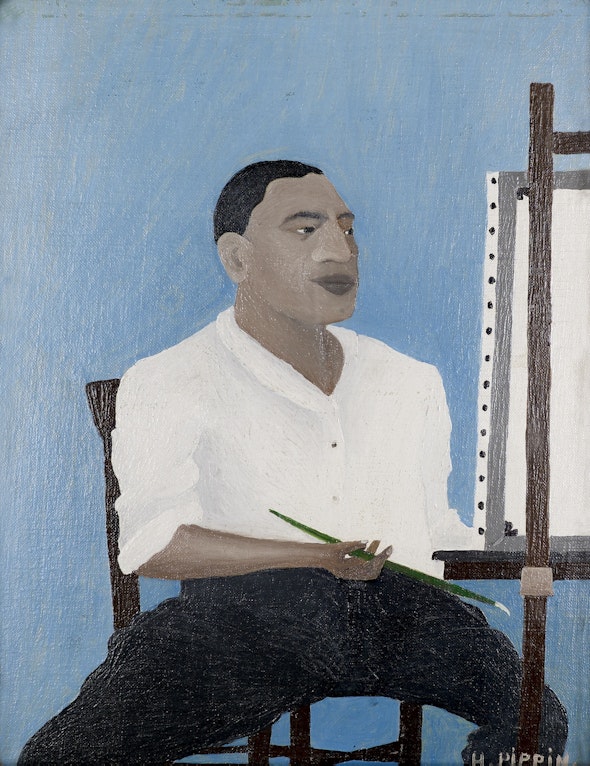

Horace Pippin. Self-Portrait, 1941. Oil on canvas board. Collection Buffalo AKG Art Museum, Room of Contemporary Art Fund, 1942

In the late 1930s and into the 1940s, Pippin became a regular fixture in American art exhibitions. After a solo exhibition at the Chester County Community Center in 1937, he garnered a national profile as the only artist of color to be included in MoMA’s 1938 exhibition Masters of Popular Painting.⁶ Despite the segregationist practices of the American art world in the interwar period, Pippin’s work was regularly included in American art exhibitions at powerful institutions such as the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.⁷ Pippin also exhibited his work in the historically Black spaces of Atlanta University and Philadelphia’s Pyramid Club, and in trailblazing exhibitions of Black art at the University of Modern Art in Boston and other influential cultural organizations.⁸ Alain Locke—the philosopher, scholar, and thinker most widely known for his founding role in the New Negro Movement—considered Pippin a key figure in his intellectual conception of the importance and aesthetic quality of Black folk art.⁹

Pippin and Dr. Barnes

Pippin’s ascent in the art world is often credited to the art critic Christian Brinton. As the story goes, Brinton spotted Pippin’s work in the window of a local store in West Chester.¹⁰ Art historian Jennifer James Marshall argues that this story structures a relationship between Pippin and Brinton that implies Pippin’s artistic talent would not have been discovered without Brinton’s discerning eye; indeed, the two were so connected that Brinton was even given credit in Pippin’s short obituary in the New York Times.¹¹ Furthermore, Brinton is positioned as having seen something in Pippin’s talent that the artist’s friends, family, and neighbors had not—thereby implying that Brinton’s expensive big-city taste was somehow better and more evolved.

Dr. Barnes and Pippin met through Robert Carlen, a Philadelphia-based art gallerist and dealer. Barnes began to purchase Pippin’s works in 1940 and soon after invited him to study at his foundation.¹² Barnes considered his patronage of Pippin integral to the artist’s success.¹³ In his catalogue essay for Pippin’s second show at Carlen Galleries, Barnes claimed there was only “one explanation” for the seemingly more mature quality to his work: “Pippin has moved from his earlier limited world into a richer environment filled with the ideas and feelings of great painters of the past and present.”¹⁴ The richer environment that Barnes is referring to here is the galleries of his own collection.

Horace Pippin. Supper Time, c. 1940. Oil on burnt-wood panel. BF985

A Closer Look at Supper Time

Supper Time is a simple composition depicting a family around the dinner table. The palette is limited, with only five colors present in the image: white, pink, blue, black, and brown. Pippin cleverly used the underlying wood panel for the table’s surface, the skin of the figures, and the window on the right-hand side. Lines incised with a burning tool delineate the transitions between the human skin and the windowpane. The image has a sort of symmetry, with bright white accents flanking both sides of the painting. The balance pulls the eye to the center of the scene, focusing on the relationships between the figures. The family members interact with each other, giving an emotional tenderness to the scene. The child reaches for a glass of milk while the father figure gazes warmly over his cup of coffee. His expression is the only visible one in the composition, and Pippin took the time to burn a massive smile into his face.

Supper Time, painted in 1940 at the height of Pippin’s relationship with Dr. Barnes, marks a transitional moment in the artist's career. As Pippin had started moving from burnt-wood panels to canvas supports at this time, Supper Time provides a mature example of his pyrographic practice. Earlier works, such as We Were On His Trail As the Sun Went Down (The Bear Hunt) (c. 1925–30, Chester County Historical Society), also use unfinished wood to construct elements of the composition, seen in the figure of the bear, pieces of wood, and small rocks in the foreground. Colors, much like in Supper Time, are minimal and blocky.

However, Supper Time demonstrates a more sophisticated use of pyrography. Pippin combined different techniques, burning lines deep into the panel and creating others that only kiss the surface. This textured layering demonstrates that the artist's understanding of the medium and skill had grown significantly since The Bear Hunt, wherein his use of burnt line was limited to outlines of shapes and forms. Pippin also added a drawer to the table in Supper Time, adding depth and space through a minimal, modernist intervention of simple lines.¹⁵

¹ Wattenmaker, Richard J., American Paintings and Works on Paper at the Barnes Foundation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 305.

² Horace Pippin, “Story of My Life,” as quoted in Gatecrashers: The Rise of Self-Taught Artists in America, auth. Katherine Jentleson (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2020), 210.

³ Missy Sullivan and Volker Janssen, “A Harlem Hellfighter’s Searing Tales from the WWI Trenches,” History.com, May 25, 2018, https://www.history.com/news/harlem-hellfighters-horace-pippin-tales-from-wwi-trenches.

⁴ Ibid; Wattenmaker, American Paintings and Works on Paper at the Barnes, 305.

⁵ Ibid, 305.

⁶ Jennifer Jane Marshall, “Find-and-Seek: Discovery Narratives, Americanization, and Other Tales of Genius in Modern American Folk Art,” in Outliers and American Vanguard Art (Washington, DC: University of Chicago Press and National Gallery of Art, 2018), 359.

⁷ Katherine Jentleson, Gatecrashers: The Rise of Self-Taught Artists in America (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2020), 77.

⁸ Ibid, 78.

⁹ Ibid, 79, 112; Later in his short career, Pippin also did more commercial work for advertisements and even a small spread for Vogue magazine. For more information, please see Jentleson and Monahan.

¹⁰ Marshall, Outliers and American Vanguard Art, 57.

¹¹ “Horace Pippin, 57, Negro Artist Dies,” New York Times, July 7, 1946.

¹² Wattenmaker, American Paintings and Works on Paper at the Barnes Foundation, 307.

¹³ Jentleson, Gatecrashers, 82.

¹⁴ Albert C. Barnes’ Introductory Text to Carlen Galleries Exhibition on Pippin, 1941, Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia, PA.

¹⁵ Thank you to Barbara Buckley for her helpful conversation and insights into Pippin and the physical process of working in pyrography.

¹⁶ Judith Dolkart, “Distinctly American: Albert C. Barnes and Horace Pippin,” in Horace Pippin: The Way I See It, ed. by Audrey Lewis (New York: Scala Arts Publishers, 2015): 27.

¹⁷ Albert Barnes, Introductory text to Pippin’s Exhibition at Carlen Galleries, March 1941, Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia, PA.

¹⁸ Anne Monahan, American Modern, 2–3.

¹⁹ Lynne Cooke, John Beardsley, Katherine Jentleson, Faheem Majeed, “Black Folk Art: A Curatorial Roundtable,” in Outliers and American Vanguard Art, (Washington, D.C.: University of Chicago Press and National Gallery of Art, 2018), 70.

²⁰ Ibid.

²¹ Ibid. The definition of what is American or what qualifies as American in style is hotly debated and outside the scope of article.

²² Albert C. Barnes’ Introductory Text to Carlen Galleries Exhibition on Pippin, 1940, Albert C. Barnes Correspondence, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia, PA.

²³ Historians Linda Gordon and Felix Harcourt have done different studies on the way that the KKK used mass culture and popular politics to impact the United States in the beginning of the 20th century. Felix Harcourt, Ku Klux Kulture: America and the Klan in the 1920s (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017); Linda Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition (New York: Liveright, 2017).

²⁴ Jentleson, Gatecrashers, 110.

²⁵ Alain Locke, The Negro in Art: A Pictorial Record of the Negro Artist and of the Negro Theme in Art (Washington, DC: Associates in Negro folk education, 1940), 10.