Greek. Head of Young Girl, 3rd–1st century BCE. Barnes Foundation A56

From Athens to the Barnes:

The Travels of a Young Girl

By Madeleine Glennon, PhD, Postdoctoral Research Fellow

In the Barnes collection, every painting and object is positioned in a specific way. Dr. Albert Barnes was very intentional about how his collection was viewed and made sure that every piece was in the correct place, in keeping with his educational methods. But sometimes viewing the works of art in the galleries from a different vantage point provides us with new information. Walking around a sculpture, for example, can reward viewers with new details and a complete picture of the work.

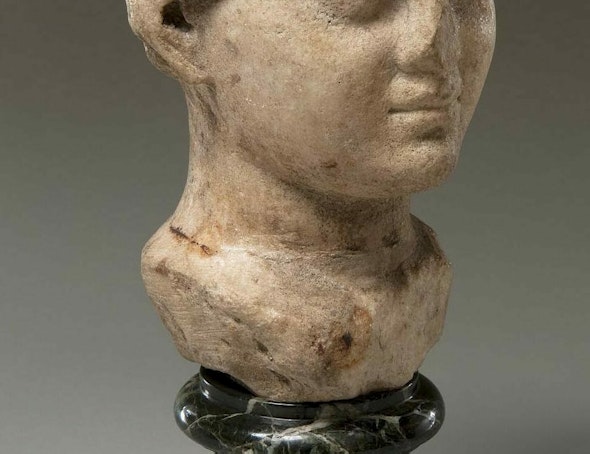

Such is the case with Head of Young Girl (Fig. 1). On display in Room 16, this ancient Greek statue fragment is shown inside a glass vitrine, surrounded by other fragments of ancient sculpture, Greek vases, and figurines (Fig. 2). Viewers can observe the face of the head, which, at first glance, appears to have come from a freestanding statue of a young girl. But closer examination by conservators and researchers has revealed details that, while invisible to the viewer in the gallery, give us a much clearer picture of the long and fascinating life, and afterlife, of this object.

Fig. 1. Head of Young Girl, 3rd–1st century BCE. Barnes Foundation A56

Fig. 2. Detail of the display case in Room 16.

Ancient Origins

Ancient art is often open to interpretation. The artists who created the Greek statues and vases on display in museums today lived over 2,000 years ago and, except in rare circumstances, did not leave any information about why, how, or for whom these works of art were made. Because of these factors, studying ancient art can be both frustrating and fascinating. In the best cases, an archaeologist or art historian may have provided information about when and where an ancient object was found in an excavation; this is called archaeological provenance. Knowing whether an ancient vase was found in a domestic context, such as a house, or a religious one, such as a temple, can give us invaluable information about its function in antiquity. Unfortunately, this information wasn’t always preserved for ancient objects on the art market in the early 20th century, when Dr. Barnes was collecting many of his objects, as archaeology was still a new discipline. When studying works like Head of Young Girl, we must use our art historical investigative skills to come up with a probable history of its life. This is where it is especially beneficial to observe ancient art up close and from all angles.

Going into our investigation, we had some knowledge about Head of Young Girl and how it came to Philadelphia. Records in the Barnes archives show that, in 1923, Dr. Barnes purchased a large group of Greek, Roman, and Egyptian antiquities from an art dealer in Paris named Georges Manolakos. The head was likely part of this purchase.

But another discovery was made in our conservation lab. A paper tag adhered to the bottom of the head’s base has a handwritten note that reads, “Paros--anc. grec. IIIe av J.C. Cabinet du C de Moüy Ministre de France en Grèce d. 1880 à 1886.” (There appear to be more words beneath this section, but the label has been damaged and they are not legible.) Charles de Moüy was the French ambassador to Greece (1880–86) and Italy (1886–88), though not much is known about his life or collecting practices. If the head was part of de Moüy’s collection while he was based in Athens, it is likely that it came from Athens as well.

The label mentions Paros, a Greek island in the Cyclades famous for its fine white marble. Based on visual analysis, however, the marble used for the head is more likely from the quarries on Mount Pentelikon in Attica. Pentelic marble is known for its creamy white color (which can take on a yellowish hue with age, as seen on the head’s surface), medium-size grains, and popularity in ancient Athens. Famously, the Parthenon on the Acropolis is made of Pentelic marble. The use of Pentelic marble for the Barnes head is further evidence that it came from Athens.

A Marble Head of a Girl

The subject appears to be a young girl, with facial features that, although worn and damaged, are soft and youthful. The mouth is closed and unsmiling, but the lips are plump and the expression appears serene. The eyes have thick upper and lower lids and no visible traces of irises or pupils—these would have been added in paint in its original appearance. The hairstyle, however, is the feature that most strongly points to a young female; it is parted at the center, with soft waves along the forehead and behind the ears, and held back with a headband (fillet).

But a look behind the head allows us to appreciate this fragment for more than its aesthetic beauty and the technical skill required to make it. The hairstyle does not continue, as we might expect, on the back; instead, we find two flat surfaces, sharp tool marks, and a roughly drilled hole (Figs. 3, 4). What does this mean? Why would an artist take such care with the face but leave the back unfinished? The answer lies in the original display context of the head, which was indeed not meant to be viewed frontally or in the round, but at a specific angle as part of a deep relief. The flat surface of the head denotes where it was originally attached to the background of a relief scene. Based on the marble and carving style and details, the head was likely part of an Attic fourth century BCE grave stele (tombstone), perhaps from a cemetery in Athens.

Fig. 3. Alternate view of Head of Young Girl, showing flat surfaces.

Fig. 4. Detail of tool marks and drilled hole.

The Life and Afterlife of a Young Girl

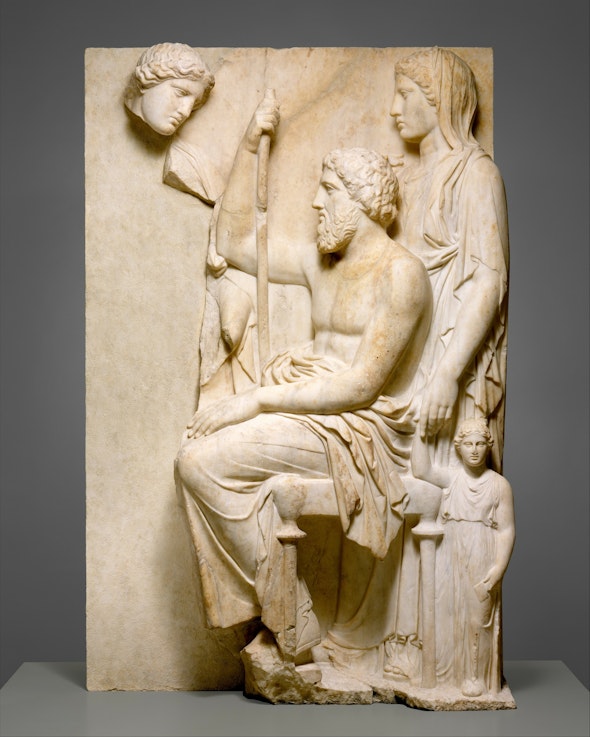

In fourth century BCE Greece, stelai were the preferred grave marker of the elite, especially in and around Athens. Excavations in the Kerameikos cemetery on the outskirts of ancient Athens have produced some of the finest examples of these monuments, which often depicted not only the deceased but also members of their family and attendants (Fig. 5).¹ Graves of children often included images of dolls or pets.² One example is the stele of Demainete, a young girl who holds a partridge (she is identified by an inscription) (Fig. 6).³ Carved in deep relief, Demainete is depicted with her face in three-fourths view, a common arrangement on grave reliefs at this time.

Though Head of a Young Girl is displayed in the round at the Barnes, the appearance of the back of the head indicates that it was part of a three-fourths-view relief, like Demainete. The flat, angled surface (Fig. 3) is likely where the head met the flat background of the relief before it was removed. In this arrangement, the girl is not meant to be viewed head-on, but from an angle (as in Figs. 5, 6). Deep gouges on the back of the head may indicate the force with which the head was removed from the relief, either in antiquity or, more likely, to prepare it for the art market.

Fig. 5. Marble Grave Stele with a Family Group, c. 360 BCE. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig. 6. Grave Naiskos of Demainete with an Attendant Holding a Partridge, c. 310 BCE. Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Commemorating the dead was a complicated process in ancient Greece. If the proper rites were not followed, the spirit (psyche) of the deceased would not make its way to the Underworld. Most of the grave markers that survive in the archaeological record belonged to members of the elite, whose wealth paid for large, elaborate monuments.⁴ In cities such as Athens, large-scale marble reliefs became the norm for the funerary markers of the upper classes. Hundreds of examples of these graves have been excavated in the Kerameikos cemetery, which, in antiquity, occupied the area directly outside of the city walls of Athens, as was the custom for ancient cemeteries (it was also the potters’ quarter and the origin of the word “ceramic”). The road leading up to the Dipylon Gate, a major entry point of the city, was lined with prominent grave markers.

If Head of a Young Girl did belong to such a grave relief, this was the first of multiple contexts. At some point in its life, the head was removed from its grave marker and corresponding body, resulting in damage to the back. The area below the neck was smoothed, and the fragment was repurposed into a bust. It is possible that this process occurred in antiquity and the head was displayed as a Roman funerary bust. What about the large hole in the back of the head? The hole was made with a drill and has evidence of mortar inside it, suggesting that it came from a modern restoration. A previous owner or an art dealer likely drilled the hole to attach the head to a wall for display.

Evidence of iron on the neck (visible in Fig. 7) suggests that a metal band was applied to the surface for some time. The purpose of this is unclear, but it may point to a secondary or tertiary context for the head as a repair or part of a display. However, the head could have been removed from a damaged grave relief and recarved in the 19th century before being sold on the art market. Ancient stone reliefs and sculptures were often broken into smaller pieces to make them easier to sell (a practice that continues today in the illicit antiquities market).

Fig. 7. Detail of evidence of iron on the neck of Head of Young Girl.

Looking Further

Sometimes, simply looking at a work of art from a different angle can change our understanding of how it was created and originally used and seen. The art historians, researchers, and conservators at the Barnes have the great privilege of getting to see these alternative and often illuminating views. The next time you are at the Barnes, think about what other secrets may be hiding behind the scenes of the paintings and sculptures you are seeing. Dr. Barnes had a specific vision for the display of his collection, but our work allows us to expand beyond this and bring new information to light.

Endnotes

¹ Paul Zanker, Afterlives: Ancient Greek Funerary Monuments in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 74–75, no. 18 (New York: Scala Publishers, 2022)

² Janet Burnett Grossman, “Forever Young: An Investigation of the Depictions of Children on Classical Attic Funerary Monuments,” Hesperia Supplements 41: 309–22 2007. And John H. Oakley, “Children in Athenian Funerary Art During the Peloponnesian War,” in Art in Athens During the Peloponnesian War, edited by O. Palagia, 207–235 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

³ Janet Burnett Grossman, Greek Funerary Sculpture: Catalogue of the Collections at the Getty Villa, 69–70, no. 24 (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001)

⁴ Robert Garland, “The Well-Ordered Corpse: An Investigation into the Motives Behind Greek Funerary Legislation,” in Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 36: 1–15, 1989. And The Greek Way of Death (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985)