Philippe Parpette. Flowerpiece in a Glass Vase (detail), 1790s, oil on canvas. BF556

Flowerpiece in a Glass Vase: A Botanical Investigation

By Amy Gillette, PhD, collections research associate

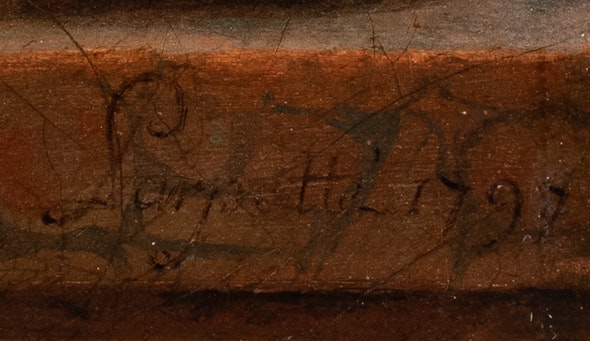

You can find the lush bouquet depicted in Flowerpiece in a Glass Vase on the west wall of Room 15 (Figs. 1a,b). Freshly filled with water—notice the droplets along its stem—the vase holds an assortment of flowers, including peonies, roses, daffodils, anemones, lilacs, myrtle, hellebores, forget-me-nots, delphiniums, and a glorious red-and-yellow tulip. It shares a marble-topped counter with two fuzzy peaches and bunches of green and purple grapes. This painting was unattributed, until recently, when our team identified the signature at the bottom right, on the edge of the counter, as that of the 18th-century French painter Philippe Parpette (active 1755–1806). The artist also recorded the date, but the last digit was hidden by materials applied during a restoration that took place before Albert Barnes purchased the painting. It was recently revealed again by a localized conservation treatment (Fig. 2), and we now know that the artist dated the painting 1797.

Fig. 1a. Philippe Parpette. Flowerpiece in a Glass Vase, 1797. Oil on canvas. BF556

Fig. 1b. Room 15, west wall, of the Barnes collection. Flowerpiece hangs below BF555, a very similar work that Dr. Barnes purchased at the same time. The artist is currently unknown but might be Parpette or one of his close colleagues. Dr. Barnes likely purchased the works to illustrate how French painters adapted the Dutch still-life tradition.

Fig. 2. A recent photograph of Parpette’s signature and the newly uncovered date.

Parpette trained as a painter at the Chantilly Porcelain Manufactory, established around 1725 by Louis-Henri de Bourbon, Prince of Condé.¹ In 1755, he began working at a porcelain factory in Vincennes, where, according to that year’s register, Parpette could “use color well and draw a little, but he promises to improve, [and] has a sweet character, quiet and hard-working.”² Two years later, he vanished from Vincennes, apparently moving to Paris to work as an enameler, a decorator of snuff boxes, and an oil painter.³ But Parpette returned to porcelain painting after the factory, now owned by King Louis XV, moved to Sèvres. There, he became a chief flower painter and worked on key commissions, including jeweled cups and saucers with portraits of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette. He also collaborated with with botanical scientists and illustrators to create stock compositions to be used for oil paintings and luxury items, like this teapot.

Though Flowerpiece is painted with exquisite precision, the work is not as “natural” as it first appears.⁴ Eighteenth-century viewers would have noticed the unlikely combination of flowers and fruits. For example, daffodils and tulips blossom early in the spring, while peaches ripen in the summer and grapes in the fall. Further, the fruits and flowers are native to different geographic regions and appear in several stages of maturity, from lilac buds to bursting grapes. Flowerpiece’s hyperrealism signals that it has layers of meaning beyond surface level.

The flowers painted by Parpette were likely influenced, in part, from medieval symbolism. See, for example, the 15th-century painting Madonna and Child (BF852), a jewel-like depiction of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child posed by a stream in a paradisiacal garden (Fig. 3). Here, lilies symbolize the purity of Mary, roses her love, violets her humility, and the apple and fig trees the “fruit of her womb” (Christ).⁵

Fig. 3. Unknown artist (German). Madonna and Child by a Stream, late 1400s. BF852

Naturalistic fruits and flowers also flourished in the margins of late medieval prayerbooks, such as this page from the Spinola Book of Hours, where the Virgin and Child are framed by carnations (love), periwinkles (virtue), and thistles (mother’s milk, on account of their white sap) (Fig. 4). During the same period, some nuns created three-dimensional depictions of enclosed gardens—tableaux of holy figures set in armatures of artificial flowers and fruit (especially roses and lilies, as well as grapes for Christ’s Passion), sewn from silk and silver thread and adorned with semiprecious stones and sequins.⁶ See, for example, the Enclosed Gardens of Mechelen, at the Museum Hof van Busleyden.

Flowerpiece and its medieval forerunners also belong to a long tradition of botanical illustration. The earliest known account thereof, in the Natural History (77–79 CE) by the Roman author Pliny the Elder, praised the work of certain artists but noted the impossibility of depicting plants holistically:

[The artists] Crateuas, Dionysius, and Metrodorus adopted a most attractive method [of botanical illustration] . . . for they painted likenesses of the plants and then wrote under them their properties. But not only is a picture misleading when the colors are so many, particularly as the aim is to copy Nature . . . in addition, it is not enough for each plant to be painted at one period only of its life, since it alters its appearance with the fourfold changes of the year.⁷

Fig. 4. Unknown artist (Flemish, Workshop of the Master of the first Prayer Book of Maximilian). The Virgin and Child in the Spinola Hours, MS Ludwig IX 18, fol. 239v, tempera, gold, and ink, c. 1510–20 (Getty Museum)

Botanical illustration nevertheless thrived through the late antique and medieval periods, often in manuscripts of the then-authoritative treatise De materia medica, written c. 65 CE by the physician-pharmacologist Dioscorides of Anazarbos. An early, and resplendent, example is the Vienna Dioscorides made for Anicia Juliana, the wealthiest person in Constantinople during the reign of Emperor Justinian (r. 527–565 CE).⁸ Manuscripts were used and copied through the Middle Ages, as templates for flowers in religious imagery as well as for medical practice (note the later Arabic glosses to the Greek text on this page of the Vienna Dioscorides).⁹

Beginning around 1500, the rise in global travel expanded the known botanical world and sparked more interest in the field. These conditions led to the propagation of the florilegium, an illustrated botanical book of principally ornamental purpose,¹⁰ and to the genesis of the standalone still life. The latter, which “sought to invest the disparate objects of nature with a pictorial logic of their own,” transformed medieval religious symbolism into more general meditations on human existence.

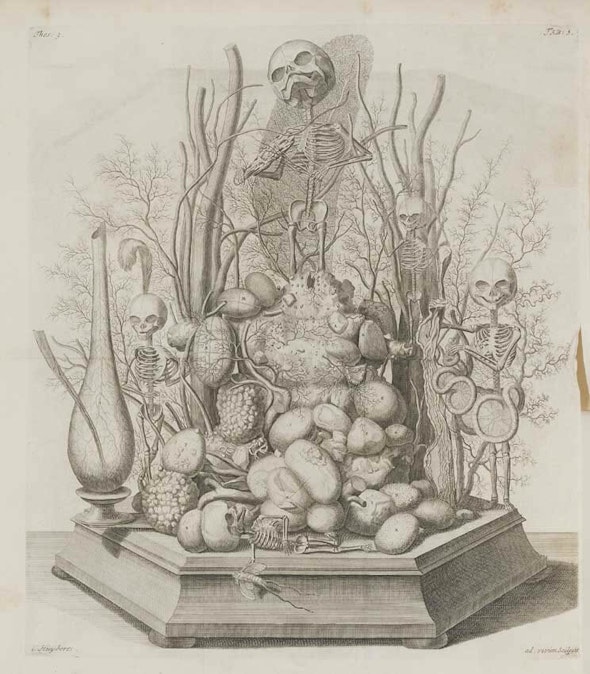

An eminent flower painter of this time was Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750), whose profound understanding of floral anatomy “earned her an unparalleled reputation among the tulip-crazy merchant class.”¹¹ Her expertise emerged from working with her father, Frederik Ruysch, a professor of botany and anatomy in Amsterdam. Rachel helped him construct three-dimensional still lifes using human, animal, and botanical materials, which straddled scientific and metaphysical inquiry (recalling, after a fashion, the medieval enclosed gardens). Frederik described one of these creations (Fig. 5): “We encounter a Walnut Pedestal, on which rests an artificial cliff-scape, made from human stones; the base of this is natural stone.”¹² On the cliff are arranged skeletons of fetuses who brandish trees of arteries, stems of grass, and tissues extracted from a woman’s bladder. The skeletons address the viewer: one holds a bone and the caption “Ah, fate! Ah, bitter fate!” Frederik continued:

At the foot of this cliff lies a Skeleton, about three and a half months old, whose hand holds a . . . mayfly, which is called Ephemeris . . . and which is said to be newly born in the morning, youthful at noon, and worn out with age & dead by evening. And just so, the brevity of our life is expressed by this insect, held in the hand of the said Skeleton. . . . Note: the gestures of this little Skeleton are most elegant, since attention to nature has not been neglected.¹³

Fig. 5. An allegorical tableau by Frederik Ruysch composed of human fetal skeletons, kidney stones, bladder tissue, and other organic material; engraving by Cornelius Huijberts, from Ruysch’s Thesaurus Anatomicus, 1703–1715 (Wellcome Collection, London)

Fig. 6. Note the pineapple in this floral still life. Corneille van Spaendonck. Urn of Flowers and Fruit, oil on canvas, before 1795 (Musée Cognacq-Jay, Paris)

By the time Parpette painted Flowerpiece, botany had become an empirical science centered in Paris, and the wide circulation of Carl Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1735) had further enchanted Europe’s middle and upper classes with horticulture.¹⁴ The results of this fascination were both epistemological and sensual, leading to connoisseurship of botanical specimens, their cultivation in greenhouses, and even greater patronage of floral imagery on canvas and luxury tableware. (Also, speaking of horticulture’s popularity, scenes similar to Flowerpiece painted by Parpette and his colleagues at Sèvres included a particularly beguiling specimen: the pineapple (Fig. 6). A tropical fruit, pineapples were rare in Northern Europe to the extent of being objects of status. Those who couldn’t afford their own pineapple, but wished to appear as though they could, had the option of renting one for an evening to display as a centerpiece for a party.¹⁵)

Parpette’s Flowerpiece unites the authority of botanical science with visual pleasure, by re-creating the wonders of nature in art.¹⁶ And, in 2018, Flowerpiece itself was re-created as the central motif of a mural in North Philadelphia.¹⁷ The mural developed out of a workshop taught by Barnes instructors on the still life within the context of the criminal justice system, with the collaboration of Mural Arts Philadelphia, artist Phillip Adams, and inmates at the State Correctional Institute in Graterford, Pennsylvania. Called Still Life, it invites viewers to contemplate time, existence, and beauty, and transform them in light of their own experiences.

Endnotes

¹ Claire Le Corbeiller, “Chantilly,” in Linda Horvitz Roth and Le Corbeiller, French Eighteenth-Century Porcelain at the Wadsworth Atheneum: The J. Pierpont Morgan Collection, exh. cat. (Hartford: Wadsworth Atheneum, 2000), 34–50.

² Philippe Parpette (Getty Museum).

³ “Parpette, Philippe,” Benezit Dictionary of Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

⁴ Jean Beaudrillard, Simulacra and Simulations (1981).

⁵ See the author’s white paper for BF852, Wheelock, Botany to Bouquets (NGA, 1999), and https://udayton.edu/imri/mary/h/herbs-and-flowers-of-the-virgin-mary.php.

⁶ Barbara Baert, “Revisiting the Enclosed Gardens of the Low Countries,” Textile: Cloth and Culture 2016, 4.

⁷ Qtd. in Heather MacDonald, “Information and Illusion: Botany and Painting at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century,” in Working Among Flowers: Floral Still-Life Painting in Nineteenth-Century France, ed. eadem and Mitchel Merling (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 3, quoting Pliny, Natural History, XXV, 8.

⁸ Leslie Brubaker, “Anicia Juliana and the Vienna Dioskorides,” in Byzantine Garden Culture, ed. Antony Littlewood, Henry Maguire, and Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 2002), 189–214.

⁹ See, e.g., Celia Fisher, Flowers in Medieval Manuscripts (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004).

¹⁰ MacDonald 2014, 5–12.

¹¹ Bailey 2012, 140.

¹² Joanna Ebenstein, ed., Frederick Ruysch and His Thesaurus Anatomicus: A Morbid Guide (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022), 149.

¹³ Thesaurus Anatomicus, 151.

¹⁴ MacDonald 2014, 5–6, 9–10. Linnaeus divided plants into 24 genera based on their stamens and pistils (that is, their reproductive structures); the illustrations of Systema naturae accordingly emphasized flowers’ blossoms. MacDonald cited Michel Foucault’s characterization of Linnaeus (who vehemently opposed scientific illustration) as a paradigmatic premodern naturalist “concerned with the structure of the visible world and its denomination according to characters” (i.e., postvisual, taking place in the realm of language). But “Linnaean botany was, in practice, immersed in a field of visual and material culture” in which “the image was a privileged source, method, and product of botanical inquiry.” See Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (New York: Vintage Books, 1994); Martin Kemp, “Taking It on Trust: Form and Meaning in Naturalistic Representation,” Archives of Natural History 17 (1990): 127–88.

¹⁵ See, e.g., https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/65506/super-luxe-history-pineapples-and-why-they-used-cost-8000, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-53432877, and https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/history-housewarming-pineapple-symbol.

¹⁶ Jeannene Przyblyski, “French Still Life and Modern Painting, 1848–1876” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1995), 137, qtd. in MacDonald 2014, 11.

¹⁷ For Still Life (2018): https://www.muralarts.org/artworks/still-life/.