Fig. 1. South wall of Room 16 of the Barnes Foundation, detail of ensemble.

The Life and Death of Tantwenemherti:

Reconstructing an Egyptian Priestess’s Coffin

Carl Walsh, Postdoctoral Research Fellow

May 2022

In Room 16, directly opposite the north doorway, a colorful image of fantastical creatures and dangerous beasts occupies a gilded wooden frame (Fig. 1). Though the work is displayed like a painting, it is actually part of an ancient Egyptian coffin (BF468). The framed coffin fragment, like other works in the collection, is hung without contextual information, encouraging viewers to make visual connections between the ancient work and the paintings, metalwork, statuary, and furniture positioned on the same wall. The unknown artist’s use of vibrant yellows, reds, and greens, for example, echoes in Adolphe Joseph Thomas Monticelli’s The Offering (BF312),Chaïm Soutine’s Still Life with Flowers (BF269), and William James Glackens’s Lenna with Basket of Flowers (BF338). Similar uses of compartmental color are evident in the Japanese and Chinese painted manuscripts and in Alexis Gritchenko’s Landscape (Trees and Goats) (BF428). A hieroglyph painted on the coffin fragment is mirrored in the long, thin shape of a French metalwork (01.16.44).

Dr. Barnes’s careful arrangements encourage close looking and cross-cultural comparison, but this research project provided an opportunity to remove the work from its frame for individual study. This allowed us to discover a good deal of decoration on the reverse side, and gave clues about the object’s purpose and information about the deceased.

Fig. 1. The coffin fragment on the south wall of Room 16 of the Barnes Foundation (far right).

What can we see on the coffin fragment?

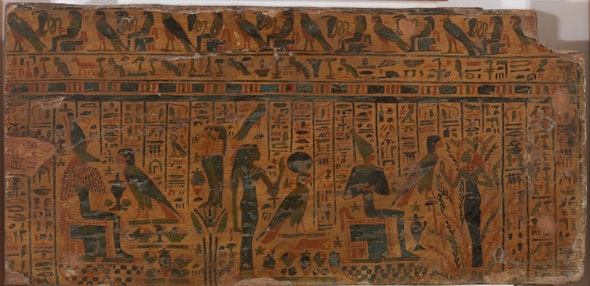

The visible side of the fragment presents two scenes divided by a blue register, or line (Fig. 2). The outstretched wings of a bird—most likely representing a vulture goddess such as Mut or Nekhbet—border the top of the upper scene. On the viewer’s right, a seated jackal represents Anubis, the god of embalming and cemeteries, whose green skin symbolizes the regenerative forces of nature. Anubis occupies a rectangular throne (for a similar example, see A421) decorated with a feather pattern in alternate rows of blue, green, and red; in the corner is the sema-tawy, a hieroglyphic motif consisting of the heraldic plants of Upper and Lower Egypt—a sedge and lotus, respectively—entwined with a windpipe. Together, the motif symbolizes the cultural and political unity of the two regions of Egypt. (For more on the heraldic symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt, see our Research Note about a relief in Room 16.)

Fig. 2: Obverse side of the coffin fragment (visible in gallery).

Opposite Anubis, a ba bird perches atop a small shrine or canopic box (used to store internal organs removed during mummification); the series of hieroglyphs to its left identifies Anubis. This scene depicts the coffin owner’s ba, a concept similar to the “spirit” of the dead. Its winged form allowed the ba to join the sun god on his journey across the sky and return to the tomb at night to be reunited with the body of the dead. In this case, the ba is being received by Anubis, symbolizing the successful journey of the deceased into the afterlife.

The lower scene of the fragment presents two figures—a recumbent jackal wearing a red neck sash and a rearing cobra. The placement of these animals served a magical function, harnessing their dangerous qualities to help protect the deceased.

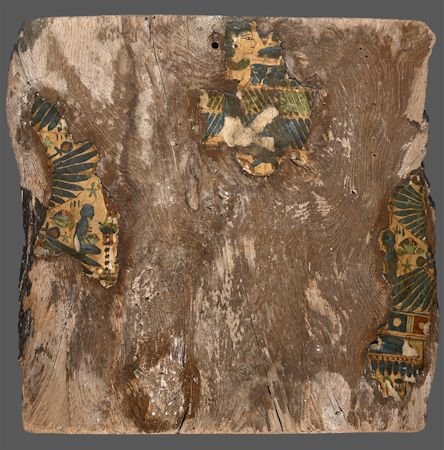

Fig. 3: Exterior side of the coffin fragment (not displayed in gallery).

The framed display at the Barnes obscures the other side of the fragment, which would have been the exterior of the coffin (Fig. 3). This exterior side is densely packed with decoration and hieroglyphic inscriptions. At the top is a frieze of alternating ba birds, falcons, and seated deities holding coiled cobras. Below the frieze, a hieroglyphic inscription contains a prayer for offerings and tells us the coffin was made for a woman named Tantwenemherti (pronounced Tant-wenem-her-ti), a priestess of a temple of Amun. It reads:

“May invocation offerings be given [to her] consisting of a thousand cattle, a 1,000 fowl, a 1,000 of linen, a 1,000 of incense, a 1,000 of ointment and a 1,000 of offerings in peace for the vindicated one, the Osiris, the lady of the House, the Chantress of Amun, king of the gods, Tantwenemherti, justified.”

Below this inscription, four funerary deities are shown receiving the ba of Tantwenemherti and surrounded by 23 columns of hieroglyphic inscription. On the far left is another depiction of Anubis on a throne, this time wearing the crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. Facing him is a ba bird representing Tantwenemherti, with offerings of food, drink, and luxury goods. Behind her, the figures perched atop a lotus flower are likely the sons of Horus, the falcon-headed god of kingship, who were responsible for protecting the deceased’s internal organs. To the right of this group is a standing female figure of the personified West, representing the cardinal direction of the netherworld, where the sun set every evening for its journey through the land of the dead. In front of her, facing right, is Tantwenemherti’s ba with a sun disk atop his head. The final group, on the viewer’s far right, includes Osiris—lord of the dead—who wears the white crown of Upper Egypt on his throne. In front of him, Tantwenemherti’s ba faces a sycamore tree goddess with a lion head, possibly Hathor, who presents a small libation vessel. The text describes deities giving offerings to Tantwenemherti. Such offerings sustained an individual in the afterlife, and the scenes rendered here would continue to provide sustenance long after her family members died and could no longer bring physical offerings to her tomb.

Reconstructing Tantwenemherti’s coffin

The coffin’s style and scenes closely parallel anthropoid coffins of the Third Intermediate Period of the 21st dynasty (1070–664 BCE), which are known for their distinctive yellow background; polychrome painting in red, blue, and green; and densely packed compositions (Fig. 4a, b, c).

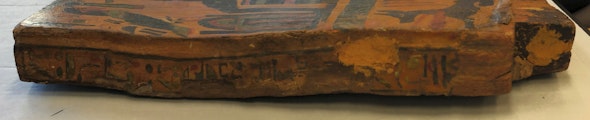

Studying the fragment outside the frame provided us with a better idea of which part of the coffin it came from. We found that the more decorated exterior side (the reverse of the panel as displayed in the gallery) was covered in layers of linen and stucco/plaster with a painted vertical column of hieroglyphic text (Fig. 5a). The inscription closely matched the offering formula quoted earlier. In addition, a large rectangular mortise slot was found on this side, interrupting the text and cut into a rabbet rim (Fig. 5a). The slot had been filled with a beige material at some point in its history. The decoration, rabbet rim, and mortise slot indicate that fragment was from the lower part of the coffin allowing the lid to be securely fastened when the coffin was carried to the tomb.

Fig. 5a: Detail of the stucco edge with painted yellow background, hieroglyphic inscription, and rabbet rim. The beige square is the filled-in mortise joint.

Fig. 5b: Dowel holes on fragment’s bottom edge, filled in with a beige material.

Fig. 5c: Interior side with exposed area of wood with filled-in dowel holes and a dovetail joint in the lower left corner.

We also noticed dowel holes on the fragment’s lower edge, which would have been used to secure a side wall (Fig. 5b). Beneath the jackal and cobra on the interior side (visible in the gallery) is an area of exposed wood with dowel holes and a large dovetail joint slot in one corner; given the angle, this is likely the point where the side wall met the footboard (Fig. 5c). The same modular construction appears in the 21st-dynasty coffin set of Nespawershefyt in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England (Fig. 6a, b). Nespawershefyt’s inner and outer coffins provide an almost exact model on how the Barnes fragment fit into Tantwenemherti’s coffin, with the side made of two planks and attached to the footboard using dovetail joints (Fig. 5c). The composition of the interior scenes support this idea as well; the register with the jackal and cobra seems to occupy space left over from the larger main scenes running along the interior side. In other coffins, this space is often at the foot and features smaller compositions or is left blank.

Fig. 6a: Outer coffin of Nespawershefyt (side view), 21st dynasty. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, England. The dovetail joint can be seen on the top left. Image © The Fitzwilliam Museum

Fig. 6b: Footboard of the coffin of Nespawershefyt with clear dovetail joints for attachment between the sides and footboard.

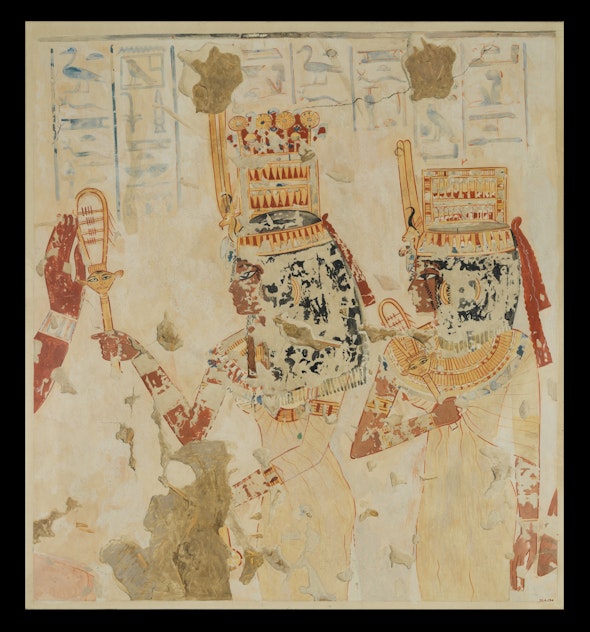

Thanks to the preservation of Tantwenemherti’s name and titles, we know that this is not the only fragment left of her coffin. Three fragments in the Museum of Grenoble, France, have her name and titles (MG 36290, MG 1993, MG 1988), and given the painting style, it seems clear that they belong to the same coffin (Fig. 7a, b, c, d, e, f). One fragment in particular has similar decoration and painting techniques for the head of Anubis, suggesting the same painter’s hand (Fig. 7f). This piece, like the Barnes fragment, probably came from the lower part of the coffin. The other two fragments likely come from the lid or a mummy board of the coffin, given their red painted interior and the appearance, on one fragment, of Tantwenemherti’s head and face (which was stolen at some point, see Fig. 7c). Most importantly, both lid fragments have painted images of Tantwenemherti herself on the interior, providing a glimpse of the person behind the coffin (Fig. 7b, d).

How were Tantwenemherti’s coffin fragments separated?

We don’t know how the fragments of Tantwenemherti’s coffin became separated. The Grenoble fragments were found or purchased in Luxor in 1842 by the French count Louis de Saint-Ferriol, an antiquities collector who amassed a sizeable collection of objects during visits to Egypt in 1841–42. On April 30, 1842, he wrote the following in a journal now digitized in the Museum of Grenoble archives¹:

“Après avoir dépecé les coffres de momie, nous disons un dernier adieu aux rives de Thèbes.” (“After dismantling the mummy coffins, we say a final farewell to the shores of Thebes.”)

His journal is light on details but mentions making contact with a few dealers in Luxor, including a Greek named Georgios Triantaphyllos and his companion, the Italian André Castellari. The former was known for dealing in mummies and coffins and entertained travelers, scholars, and prospective customers in his house on the west bank of Luxor. Perhaps the coffin of Tantwenemherti was in his possession and in poor condition, and he and Saint-Ferriol separated out desirable elements. This could explain the fragmented condition of the coffin today.²

After visiting Egypt, Saint-Ferriol displayed his antiquities collection at his castle at Uriage-les-Bain (near Grenoble); it may have included the Barnes fragment. Saint-Ferriol died in 1877, and in 1916, his son Gabriel gifted a large portion of his collection to the Museum of Grenoble, including the three pieces mentioned above. Gabriel de Saint-Ferriol likely sold other items on the art market, as objects from the collection were purchased by the Louvre between 1920 and 1940 and by dealers such as the Brummer Brothers in New York. The Barnes fragment may have traveled to a gallery in Paris or New York, where it was seen and purchased by Albert Barnes. Or perhaps Dr. Barnes acquired the coffin on a visit to the Museum of Grenoble and its curator Andry-Farcy, a friend with a shared appreciation of modern art. Or maybe Dr. Barnes saw the coffin fragments of Tantwenemherti after they went on display in 1922, along with the rest of the donated Saint-Ferriol antiquities collection. We don't know exactly where, or from whom, Albert Barnes acquired the fragment, as the object has no accompanying documentation in the archives. Its earliest mention seems to be in a 1926 list of paintings on display in the gallery.³

Fig. 8: Karnak Temple Complex, Luxor. Photo by Ahmed Bahloul Khier Galal

What can this coffin fragment tell us about Tantwenemherti?

As a chantress, Tantwenemherti held an important position in the temple of Amun at Karnak, Thebes (modern Luxor), then the largest and most influential temple in Egypt (Fig. 8). Chantresses were often high-status women and in some cases even considered daughters of Amun.⁴

They formed part of the four phyles—subdivisions of the priesthood—that worked in the temple in rotating seasonal shifts. Tantwenemherti would have performed religious songs, liturgies, and prayers as part of the temple’s daily ritual, including dancing and playing musical instruments such as clappers and sistri (Fig. 9a, b, c). Chantresses also performed in Theban religious festivals, such as the Beautiful Festival of the Valley.

Fig. 9a: Daughters of a man called Menna playing sistri, Tomb of Menna, New Kingdom, c. 1400–1352 BCE. Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig. 9b: Ivory and bone clappers, New Kingdom/Late Period, probably 1550–525 BCE. Barnes Foundation A98J and A98l

Fig. 9c: Bronze sistrum inscribed for the chantress of Sobek of Kheny, Tapenu, New Kingdom/Late Period, c. 1186–600 BCE. Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

When working, Tantwenemherti would have had an income supplied by the temple and a home in the complex. The inscriptions on the Grenoble fragments identify her as the daughter of Iwefkhonsu, a prophet of Amun, and the wife of a priest named Amenkhay (Fig. 9d). Given their positions, her family probably spent a great deal of time living and working in the temple; they were likely wealthy and may have had an additional home in the city. Her family’s wealth is of course suggested by her intricately painted coffin, for which no expense was spared. The missing face on one of the fragments was likely gilded, as seen in many other examples of this quality.⁵

Fig. 10: West bank at Thebes.

Since Tantwenemherti lived at Thebes, she must have been buried in the vast necropolis on the west bank of the Nile, across from the city (Fig. 10). The Grenoble fragments were in fact acquired there, though the location of her tomb has yet to be discovered. During the 21st dynasty, palatial economies across the Mediterranean failed, an event often termed the “Bronze Age Collapse” (1225–1175 BCE). Though Egypt appears to have adapted to the difficulties, the widespread disruption to exchange and political systems weakened the economy and lead to the decentralization of the state.⁶ As a result, family tombs became a new norm, offering lower expenses as well as protection from grave robbers.⁷ The coffins themselves were given more attention. Tantwenemherti’s highly decorated coffin included spells and scenes that would help her successfully journey to the afterlife and continue to enjoy offerings of food, drink, and luxuries even after she was forgotten. However, there are clear signs that the coffin was at some point disturbed; the missing face on her coffin lid may have been the result of robbers removing its gilded elements (Fig. 11). The picking over of her coffin and the possible dismantling by antiquities dealers may explain why the coffin is in such a fragmentary state today.

Fig. 11: Outer and inner coffins of Djedmutesankh, in which the gilding on the face, breasts, and hands has been looted, 21st dynasty, Third Intermediate Period, c. 1000–945 BCE. Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Remember her name

This piece of Tantwenemherti’s coffin played an important role in her continued existence after death by preserving her name, including images of her as successfully regenerated in the afterlife, and providing magical spells to protect and sustain her. One might ask if it is ethical to display an object so intimately tied to an ancient person’s identity and beliefs concerning death. At the Barnes, we are attempting to recapture the story of the ancient person this object belonged to, rather than display it as just an example of Egyptian visual traditions. When you look at this object in the gallery, try to see the person behind the coffin, and remember her name, Tantwenemherti.

Endnotes

¹ The journal of Louis de Saint-Ferriol can be accessed online here.

² I’d like to thank Joëlle Vaissiere, conservator in charge of ancient art at the Grenoble Museum for her invaluable help in sharing information on the provenance of their fragments.

³ Collection Information, list of paintings in the Barnes Foundation, 1926 (AR.COL.10A).

⁴ Suzanne Lynn Onstine, “The Role of the Chantress (Šmyt) in Ancient Egypt” (Ph.D., Toronto, University of Toronto, 2001).

⁵ Florence Gombert and Frédéric Payraudeau, Servir Les Dieux d’Égypte: Divines Adoratrices, Chanteuses et Prêtres d’Amon à Thèbes (Somogy éditions d’art, 2018), 128.

⁶ Kathlyn Cooney, “Changing Burial Practices at the End of the New Kingdom: Defensive Adaptations in Tomb Commissions, Coffin Commissions, Coffin Decoration, and Mummification,” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 47 (2011): 3–44.

⁷ Kathlyn Cooney, “Changing Burial Practices at the End of the New Kingdom: Defensive Adaptations in Tomb Commissions, Coffin Commissions, Coffin Decoration, and Mummification,” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 47 (2011): 3–44.