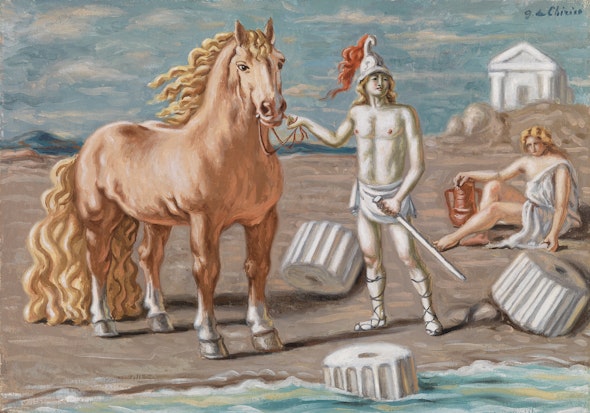

Giorgio de Chirico. Alexandros (detail), 1935. BF960. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Out of the Shadows and into the Sun: de Chirico’s Alexandros

By Kaelin Jewell, PhD, Senior Instructor, Adult Education

December 2020

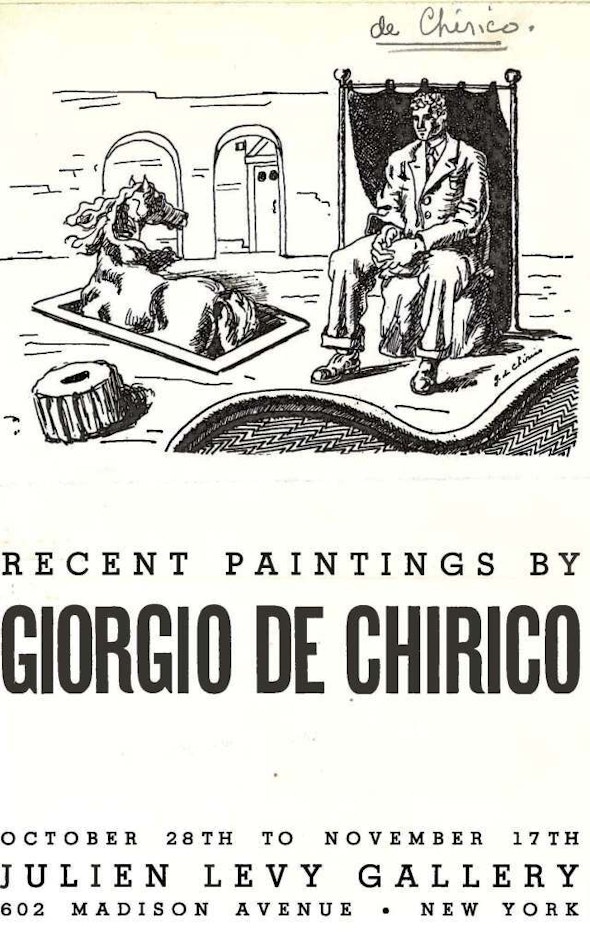

Positioned above the doorway of Room 18 is a rather mysterious painting of a horse standing at the edge of the sea (Fig. 1). A man with pale white skin holds the animal’s reins, and a woman lounges nearby. The work, titled Alexandros (BF960), was created in 1935 by the Greek-born Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico and was part of his first American solo exhibition at New York’s Julian Levy Gallery in 1936 (Fig. 2).¹ Albert C. Barnes purchased Alexandros, along with Horses of Tragedy (BF1178), before the show opened to the public.² In his introductory essay for the exhibition catalogue, Dr. Barnes was sure to note his ownership of these works and underscore their visual connections to the larger history of European painting.³

Figure 1: Giorgio de Chirico. Alexandros, 1935. BF960. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Figure 2: Exhibition catalogue from Recent Paintings by Giorgio de Chirico at Julien Levy Gallery, New York, 1936

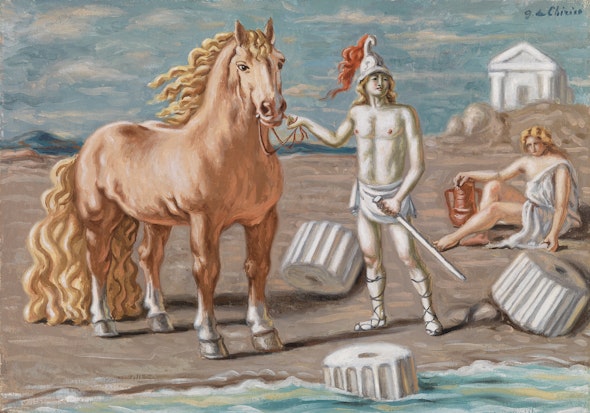

Unlike the often-enigmatic works from de Chirico’s earlier metaphysical period, Alexandros is relatively straightforward. The painting shows Alexander the Great, the famed ancient Greek king of Macedon who is known for his fourth century BCE military campaign in which his forces conquered the eastern Mediterranean, parts of central Asia, and India. De Chirico’s Alexander, however, doesn’t appear to have achieved much military success. Though he wears a red-plumed helmet and grips his sword, he appears as an unblemished youth whose skin is so smooth it almost gleams like marble (Fig. 3). The seated female, rendered in warmer peach tones, provides an aesthetic contrast. Her presence in the scene—along with the white column drums and hilltop temple—also relates to de Chirico’s penchant for quoting antiquity. She may serve as a personification of Hellas (the Greek world) more generally.⁴

Figure 3: Detail of Alexandros

The human figures are balanced on the left by a monumental chestnut-color horse with a flowing flaxen mane and tail. The space given over to this animal is notable and cause for deeper inquiry. Many ancient sources reference Bucephalus, the fearsome and imposing warhorse who carried Alexander the Great across the Mediterranean and Asia. The subject of numerous depictions throughout art history, Bucephalus is often rendered in dynamic motion, reflecting his fierce reputation (figs. 4–5). The Greek historian Plutarch wrote that Bucephalus, upon his arrival at the court of Alexander’s father, King Philip II of Macedon, was impossible to tame:

Once upon a time Philoneicus the Thessalian brought Bucephalus, offering to sell him to Philip for thirteen talents, and they went down into the plain to try the horse, who appeared to be savage and altogether intractable, neither allowing any one to mount him nor heeding the voice of any of Philip’s attendants, but rearing up against all of them.⁵

Figure 4: Charles Le Brun. Triumph of Alexander, 1665. Image © Musée du Louvre

Figure 5: Alexander the Great and Bucephalus. Detail of the Battle of Issus mosaic from Pompeii’s House of the Faun, ca. 100 BCE. Now in Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

After seeing the commotion, Alexander took his turn with Bucephalus:

Alexander ran to the horse, took hold of his bridle-rein, and turned him towards the sun; for he had noticed, as it would seem, that the horse was greatly disturbed by the sight of his own shadow falling in front of him and dancing about. And after he had calmed the horse a little in this way, and had stroked him with his hand, when he saw that he was full of spirit and courage, he quietly cast aside his mantle and with a light spring safely bestrode him.⁶

Is this the fateful moment referenced in the de Chirico painting? It’s certainly possible, given that de Chirico prided himself on his knowledge of the ancient Mediterranean. As noted by Dr. Barnes in his catalogue essay, de Chirico’s ideas were “those of a mystic poet who has assimilated the essentials of the intellectual content of the great classics of literature and painting, and has utilized them to tell us what the world of today means to him.”⁷

When we compare Alexandros with de Chirico’s earlier metaphysical works, such as The Arrival (BF377), we realize just how different the painting is (Fig. 6). Absent are the deep colors and dark shadows that rake across empty Italian piazzas. Instead, de Chirico presents an ancient landscape inhabited with fully modeled figures who are so three dimensional that they take on a sculptural quality. Despite these differences, the importance of light and, more significantly, shadow is still emphasized. Whether starkly rendered or softly realized, de Chirico’s shadows are one way the “whole mystery of volume begins to speak.”⁸ In Plutarch’s account, both the presence and absence of Bucephalus’s shadow serve as a catalyst for Alexander’s future conquests. Of shadows, specifically, de Chirico noted, “There are many more enigmas in the shadow of a man who walks in the sun than in all religions of the past, present, and future.”

Figure 6: Giorgio de Chirico. The Arrival, 1912–1913. BF377. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Alexandros also seems to be part of a larger theme in de Chirico’s works from the 1930s whereby horses and figures on seashores serve as visual metaphors for travel and long-distance journeys.⁹ Alexander may function as a historical avatar for de Chirico, who viewed his sojourn to America in Alexandrian terms. In 1939, de Chirico described the moment when he first arrived in New York, comparing the city to ancient Babylon (where Alexander the Great died in 323 BCE):

Upon arriving in New York everything that appears to you—the skyscrapers of Wall Street, the mist, the tugboats, the elongated, white, cubist architecture, properly lined-up, and reminiscent of the historical reconstructions of Babylon . . . all of this is suffused with an otherworldly light.¹⁰

Although dismissed by European critics and fellow artists as inferior to his metaphysical works, de Chirico’s horse paintings were popular with American collectors.¹¹ In his 1968 retrospective catalogue, de Chirico’s wife Isabella Far justified her husband’s horse pictures:

The horses are painted with long sweeping tails and wavy manes that fall gracefully about their necks, with an occasional loose strand fluttering in the air or resting on their foreheads. Viewers were fascinated by the regal richness of these manes and of the tails that touch the ground, by the power and beauty of these magnificent animals drawing up their bodies to their full height. Here is an astonishing vision of dream horses on some legendary beach of ancient Greece.

Here too is a deserted beach strewn with fragments of shattered columns and, on surrounding hills, temples with pure and stately lines. The temples, dedicated to the gods of Hellas, stand against the transparent sky; delicately colored with fluffy white clouds, the sky is low, near at hand, close to the earth, close to us. Lured by the beauty of myths we hold so dear, our imagination wanders in an enchanted world of divine and human mythology.¹²

Endnotes

¹ On the development of the exhibition, Recent Paintings by Giorgio de Chirico, see Katherine Robinson, “Giorgio de Chirico–Julien Levy: Artist and Art Dealer. Shared Experience,” Metafisica 7-8 (2008): 326-356.

² For a discussion of Horses of Tragedy, see the October 2018 edition of Research Notes: https://www.barnesfoundation.org/research-notes-de-chirico

³ Albert C. Barnes, “Giorgio de Chirico,” Metafisica 7-8 (2008): 725-727; orig. Recent Paintings by Giorgio de Chirico: October 28th to November 17th (New York: Julien Levy Gallery, 1936).

⁴ It’s possible that de Chirico was using Salomon Reinach’s multivolume work Répertoire de la statuaire grecque et romaine (1897-1924) as a sort of model for his classicizing images.

⁵ Plutarch, Plutarch’s Lives: VII Demosthenes and Cicero, Alexander and Caesar, trans. Bernadotte Perrin, Loeb Classical Library vol. 99 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967), Book 6, 237.

⁶ Ibid., 239.

⁷ Barnes, “Giorgio de Chirico,” Metafisica 7-8 (2008): 725; orig. Recent Paintings by Giorgio de Chirico: October 28th to November 17th (New York: Julien Levy Gallery, 1936).

⁸ For more on de Chirico and the shadow, see Victor I. Stoichita’s Short History of the Shadow (London: Reaktion Books, 1997), 144-149.

⁹ For more on this, see Maurizio Fagiolo dell'Arco, ed., De Chirico: Gli anni Trenta (Milan: Skira, 1995), 177-187; and idem, De Chirico: Gli anni Trenta (Milan: Edizioni Mazzotta, 1998), 54.

¹⁰ Giorgio de Chirico, “I have been to New York,” Metafisica no. 7-8 (2008), 683. Originally published as “J’ai été a New York,” in XX Siècle, March 1938.

¹¹ Klich, “De Chirico and Dr. Barnes,” 61. On the Metaphysical period, in which de Chirico drew inspiration from Sigmund Freud’s On the Interpretation of Dreams, the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, and artists like Arnold Böcklin and Max Klinger, see Paolo Baldacci, De Chirico: The Metaphysical Period, 1888-1919 (Boston: Bullfinch Press, 1997); and Adriano Altamira, “De Chirico, Böcklin and Klinger,” Metafisica 5-6 (2006): 51-64. For his impact on and break with the Surrealists, see Paolo Baldacci, Betraying the Muse: De Chirico and the Surrealists (New York: Paolo Baldacci Gallery, 1994); and Karen Kundig, “Giorgio de Chirico, Surrealism, and Neoromanticism,” in De Chirico and America, ed. Emily Braun (New York: Hunter College of the City of New York, 1996), 97-110.

¹² Isabella Far, de Chirico (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1968), 3.