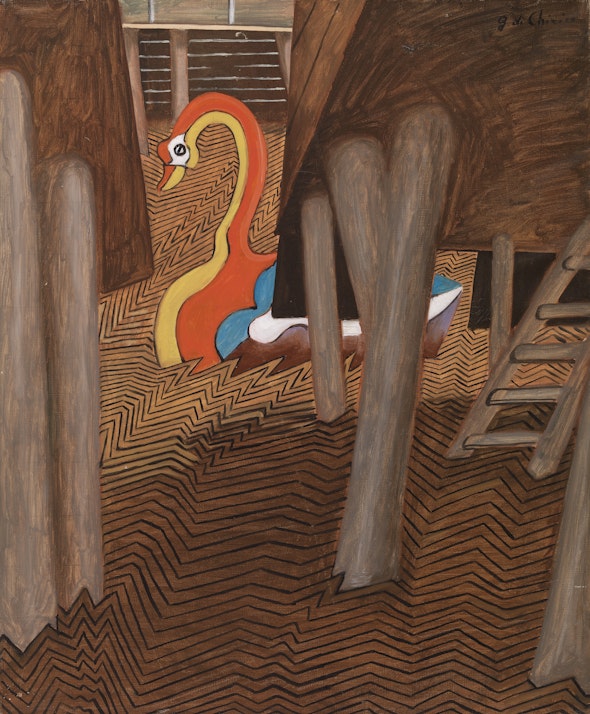

Giorgio de Chirico. The Mysterious Swan (detail), 1934. BF410. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

The Mysterious Swan

By Amy Gillette, Collections Research Associate

March 2020

In this enigmatic painting by the prolific Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978)—on display in Room 23—a vivid multicolor swan floats in zigzagging brown “water-parquet” amid stilted and off-kilter wood structures, one equipped with a ladder.

Giorgio de Chirico. The Mysterious Swan, 1934.

De Chirico created The Mysterious Swan in 1934, about 20 years after celebrated early works such as The Rose Tower (BF597, 1913), on display on the same wall. In 1935, he exhibited The Mysterious Swan and related works at the Seconda Quadriennale in Rome; he sold the painting and Two Mysterious Cabins (BF266, 1934) directly to Dr. Albert Barnes in 1937, while working in the US.¹

Giorgio de Chirico. The Rose Tower, 1913. BF597. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Giorgio de Chirico. Two Mysterious Cabins, 1934. BF266. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

How should we interpret a picture whose subject seems so straightforward yet is rendered in a style so strange? On one level, writings by de Chirico reveal that The Mysterious Swan was a pastiche of childhood memories of his seaside hometown of Volos, Greece.² The artist’s father, an engineer for Thessaly Railways, had supervised the building of a rail link between the beach and city center. Part of the project involved erecting long wood bridges over the water that supported private changing cabins, each with an interior ladder leading into the water. A squadron of white swans occupied the adjacent Anavros river, mythologized in The Argonauts.

We know, as well, that the artist’s impressions of the beach development shaped his depiction thereof; the changing cabins, for example, had fascinated him as sites of transition between civilized dress and primal nudity, and as portals into the oceanic abyss:

“I remember that the beach cabins always disturbed me and gave me a great sense of dismay. Those few steps of wood covered with algae and mold immersed less than half a meter under water seemed as though they must have been descending for leagues and leagues, down into the heart of oceanic darkness.”

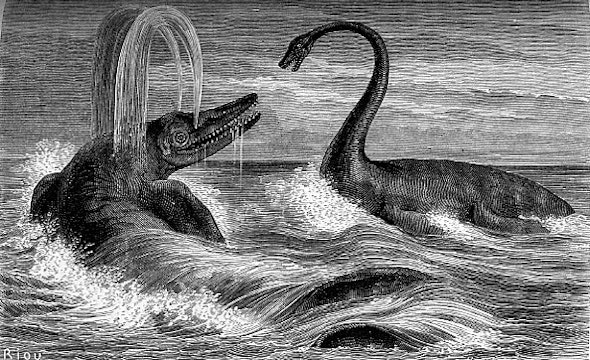

Complementing this sense of deep space and time, the polychromatic swan—“so metaphysical in its appearance”—brings to mind the illustration of a plesiosaur adorning the cover of Louis Figuier’s La terre avant le déluge (1888), a book de Chirico cherished as a boy.⁴ The zigzagging water, on the other hand, was prompted by a revelation in adulthood:

“The idea for the 'Mysterious Baths' came to me once when I happened to be in a house where the floor had been polished with wax. I watched a gentleman walking in front of me, whose legs reflected in the floor. I had the impression that he could sink into that floor, like in a swimming pool and that he could move and even swim in it. Then I imagined strange swimming pools with men immersed in a kind of water-parquet.⁵”

Illustration from La Terre avant le déluge.

The painting’s angular water, antediluvian creature, mythic river, and very title suggest that de Chirico didn’t intend for the work to be understood just literally or personally. In fact, he stated in the Seconda Quadriennale exhibition catalogue: “I continue again in my research of inventions and fantasy. To this genre belong the paintings Mysterious Baths, The Swimmers, and The Mysterious Swan.”⁷

The painter had announced the nature of this research in a 1920 self-portrait, in which he holds a sign reading “Et quid amabo nisi quod rerum metaphysica est?” (What I will love if not the metaphysics of things?) Throughout his career, de Chirico sought new ways of depicting metaphysical principles: that is, the second aspect of things, not visible to our eyes. To this end, he voraciously adapted images and ideas from ancient Greek mythologists and philosophers, medieval and Renaissance artists such as Giotto, Cennino Cennini, Raphael, and Michelangelo, as well as Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Arnold Böcklin, Max Klinger, Arthur Schopenhauer, Otto Weininger, Guillaume Apollinaire, and, above all, the great existentialist philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, with whom he personally identified.⁸

Of these sources, Greek mythology signals another level of interpretation for The Mysterious Swan. De Chirico's first iteration of the mysterious baths was a series of lithographs for the volume Mythologie (Paris, 1934, with poetry by Jean Cocteau), in which gods, giants, and galloping centaurs join the human bathers.⁹ In The Mysterious Swan properly, the bird in question probably heralds two related myths: the Argonauts, which commenced when the hero Jason lost a sandal in the turbulent waters of the Anavros, and Leda and the Swan, in which the human princess Leda was impregnated by the god Zeus disguised as a swan and gave birth to the twins Castor and Pollux (usually referred to as the Dioscuri), who became fabulously skilled horsemen as well as Argonauts. Within the scheme of de Chirico’s self-mythologizing, the Argonauts stood for his life journey, and the Dioscuri as alter egos for himself and his brother, the philosopher Alberto Savinio.¹⁰

The imagery in The Mysterious Swan, then, could be said to assert the power of mythmaking in shaping the phenomenal world (with phenomena being things as we perceive them, not how they might be, per se). This is at the heart of what de Chirico had meant when he wrote that his mysterious baths advanced his “research of inventions and fantasy” of his Mediterranean piazzas (e.g., The Rose Tower or BF377, The Arrival). From the 1910s, these paintings evoked Nietzschean metaphysics: the absence of meaning inherent to existence, offset by the power of individuals to make their own meaning and the “eternal return” of events and motifs (i.e., everything that has happened already will happen again).

Whereas the piazza paintings employed the geometries of classical architecture (and, later, the skyscrapers of New York¹¹) as thick curtains at the threshold of the material and immaterial worlds, the mysterious baths seem to have embedded metaphysics elementally in the water-parquet. They expressed the philosopher Heraclitus’s idea that “everything flows”—a precursor to the idea of eternal return, which he, Nietzsche, and de Chirico had all encountered in a bubbling fountain, aptly affirming that meanings can accumulate as events repeat. ¹²

With respect to repetition, de Chirico revisited these themes of the mysterious baths and the Mediterranean piazzas through the remainder of his career. He delivered the baths’ apotheosis in the monumental Mysterious Baths Fountain installed in Milan’s Sempione Park—a triumph of the immersion in the “strange swimming pools” of his original vision.¹³ But back in the 1930s, de Chirico occasionally fused the two scene types, most likely to express that personal and sociopolitical myths came into being on the same metaphysical continuum.

The Mysterious Baths Fountain, installed in Milan’s Sempione Park in 1973.

Photo by Pasquale Relvini

De Chirico specialist Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco remarked—briefly—of a potentially causal affinity between the baths and Horses of Tragedy (BF1178, 1935), also in Room 23: “The painting Horses of Tragedy that enters the Barnes collection—the stallion immersed in the trapezoidal pool—can also be considered a mysterious bath."¹⁴

More recently, the Barnes Foundation’s Kaelin Jewell gave further context for the relationship by linking the titular horses with those precipitating the apocalypse (Revelation 6). In effect, de Chirico’s colossal and chaotic horses indicted Mussolini’s crude exploitations of ancient history in the service of fascism, a narrative distressingly divergent from the artist’s discursive relationship with the cultural past (he reminisced in that in the early 1900s, “A great calamity was brewing: modern painting.... And about a quarter of a century later there was to be another calamity, much worse than the former: Nazism”).¹⁵ The violent-yet-generative myth Leda and the Swan recommended the swan as a convention, among post-Nietzschean thinkers, to illustrate the dualistic terms of Heraclitan strife that drive historical progression—of rebirth in the water-parquet, or on the other side of the apocalyptic veil.¹⁶

Giorgio de Chirico. Horses of Tragedy, 1935. BF1178. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Giovanni di Pietro. Sienese Government Officials Receiving an Embassy, c. 1440. BF868. Public Domain.

The display of de Chirico’s paintings in the Barnes galleries likewise contributes to new meanings. For example, the pairing of Horses of Tragedy with the 15th-century panel Sienese Government Officials Receive an Embassy (BF868) colors our understanding of gothic artistic production as much as de Chirico’s own. Further, Dr. Barnes acquired The Mysterious Swan and Horses of Tragedy at the same time he was expanding his foundation’s commitment to aesthetic experience and social justice as reciprocal goals.¹⁷ It’s therefore fortunate, for the sake of appreciating the ethical dimension of repetition, that the paintings engage each other in persistent conversation on the walls of Room 23. Their placement appears especially serendipitous in light of de Chirico’s account, published in 1938, of his 1936 visit to the Barnes.

He proclaimed that that "nothing is more difficult" than trying to visit the museum of Dr. Barnes (“a mysterious American whose face few can claim to have seen,” and “a mystic of painting in general, and modern painting in particular”) in Merion, Pennsylvania (“a wooded and tranquil place where American billionaires have erected villas and sumptuous castles”), partly because it was guarded by “the biggest and most ferocious dogs that exist in the world.”¹⁸ De Chirico continued:

“[Dr. Barnes] lives alone at his museum, with his Patagonian mastiffs, in the middle of the paintings which he so loves. He knows that the paintings will perish with him. In fact, the basement of the museum is rigged with mines. In the will of Dr. Barnes it is written that when he dies, his body must be taken to the central gallery of his museum; then, after having sent everybody away, a faithful servant, from a safe distance, will press on a button and the magnificent collection—with the mortal remains of its creator—will disperse into the air.¹⁹”

The Barnes did not, thank heavens, vanish following the death of Dr. Barnes in 1951. Visitors in the intervening decades have continued to experience de Chirico’s recurrent mysterious baths and Mediterranean monuments—and their visual statements within the Barnes collection—as agents in a cycle of constant change. This cycle is ultimately life-affirming, as the images’ meanings—past and present, global and personal—reverberate in our minds.

Endnotes

¹ Giorgio de Chirico to Nino Bertoletti, letter, reproduced in an article published in the journal La Tribuna. See Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, I Bagni misteriosi. De Chirico anni trenta: Parigi, Italia, New York (Milan: Berenice, 1991), 220-2. For further information, see: Lynda Klich, “De Chirico and Dr. Barnes,” in Giorgio de Chirico and America (New York: Hunter College of the City University of New York, 1996), 60, 65, 71.

² Martha Davidson, “The New Chirico: A Classic Romantic,” in Art News, 28 November 1936 (written in response to the 1936 Julien Levy show, in which Dr. Barnes was also involved). Davidson’s essay is reproduced in Fagiolo dell’Arco, 220.

³ Nicholas Velissiotis, “Giorgio de Chirico and the Mysterious Baths Fountain in Milan’s Sempione Park,” Metaphysical Art 9/10 (2010): 191.

⁴ Fagiolo dell’Arco, 220; Velissiotis, 196.

⁵ Velissiotis, 195.

⁶ Public domain in the USA: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Giorgio_de_Chirico,_1920,_Self-portrait,_oil_on_wood,_50.2_x_39.5_cm,_Pinakothek_der_Moderne.jpg.

⁷ “Proseguo ancora nelle mie richerche di invenzioni e di fantasia. A questo genere appartengono i quadri Bagni misteriosi, I nuotatori, e Il cigno misterioso.” Cit. in the exh. cat. II Quadriennale d'Arte Nazionale (Rome, 1935). See Mario Ursino, Giorgio de Chirico e l’antico (Rome, 2006), 65-6.

⁸ De Chirico’s identification with Nietzsche concerned not only philosophical affinity but also Nietzsche’s public breakdown in 1888 (the year that de Chirico was born) over the flogging of a horse in the Piazza Carlo Alberto, Turin (where de Chirico later lived). The Rose Tower depicts the square’s principal landmark, an equestrian statue of Carlo Alberto. See, e.g., Isabella Far, De Chirico (Milan, 1966) and Ursino 2006. Within de Chirico’s oeuvre, horses seem to act as liminal figures of Dionysian destruction.

⁹ Jean Cocteau, Mythologie (Paris: Éditions des Quatres Chemins, printed by Edmond Desjobert, Paris, 1934). De Chirico’s compositions had immediate inspiration in prints by Max Klingler: e.g., his Brahamsfantasie and Vom Tode series.

¹⁰ Sean Theodora O’Hanlan, “De Chirico and the Dioscuri: Metahistory and a Conception of Personal Mythology,” Colgate Academic Review 9.1 (2012), 57.

¹¹ Giorgio de Chirico, “Metaphysica dell’America,” in Omnibus, la rivista di Leo Longanesi (October 8, 1938). Also see Fagiolo dell’Arco, 257.

¹² A sample of the historiography on de Chirico’s water-parquet: Ursino 2006 for relations to Greco-Roman mythology; Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco’s account of its origins and development from metaphysical nostalgia; A. Ruggieri, “Interpretazione e descrizione della Fontana Bagni misteriosi secondo alcuni percorsi formali e simbolici,” in G. de Chirico. Nulla Sine Tragoedia Gloria: Proceedings of the European conference (Rome, 2002); Kathleen Robinson, “Mysterious Baths: Communicating Vessels,” in Metafisca 7 (2008) (interpretation of the baths’ “parquet water” as a physical embodiment of mystery and paradoxical conduit of human communication).

¹³ Velissiotis, 192.

¹⁴ Fagiolo dell’Arco, 122.

¹⁵ For more on de Chirico and his evolving perception of fascism in the 1930s, see Kaela Jewell, The Art of Enigma: The De Chirico Brothers and the Politics of Modernism

(University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004, 99-101.

¹⁶ See Rudiger Gorner and Angus Nicholls, In the Embrace of the Swan: Anglo-German Mythologies in Literature, the Visual Arts, and Cultural Theory (De Gruyter, 2010).

¹⁷ E.g., the mid-1930s saw the publication of John Dewey’s Art as Experience (1934), as well as the exhibition of antique metalworks as equivalents in design to the “fine” arts of painting and sculpture.

¹⁸ Merion “e un luogo boscoso e tranquilo ove alcuni miliardari americani hanno fatto costruire delle ville e dei castelli sontuosi…” where you can find “il museo del dottor Barnes”; “Nulla e cosi difficile come poter visitare tale museo.” Giorgio de Chirico, “Barnes collezionista Mistico,” L’Ambrosiano (Milan, February 16, 1938); reproduced in Fagiolo dell’Arco 1991, 220. My translation.

¹⁹ De Chirico wrote about Dr. Barnes: “è un americano misterioso la cui faccia pochi possono vantarsi di aver visto… Il dottore Barnes è un mistico della pittura in genere e della pittura moderna in ispecia.” “Egli vive la, solitario, con i suoi molossi patagoni, in mezzo ai quadri che ama tanto. Egli sa che quei quadri spariranno con lui. Infatti i sotterranei del museo sono minati. Nel testamento del dottor Barnes sta scritto che quando egli morira bisognera portarlo nella sala centrale del suo museo; indi, dopo aver fatto allontanare tutti, un servo fedel, posto a buona distanza, premera sopra un manubrio e la magnifica collezione, con i resti mortali del suo creatore, si disperdera dell’aria.” De Chirico 1938; reproduced in Fagiolo dell’Arco 1991, 220.