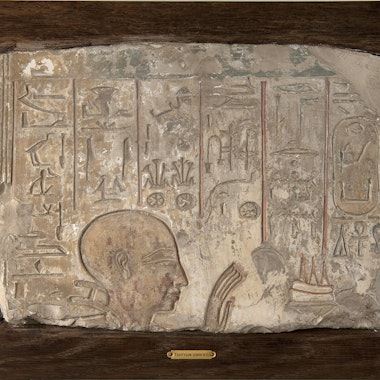

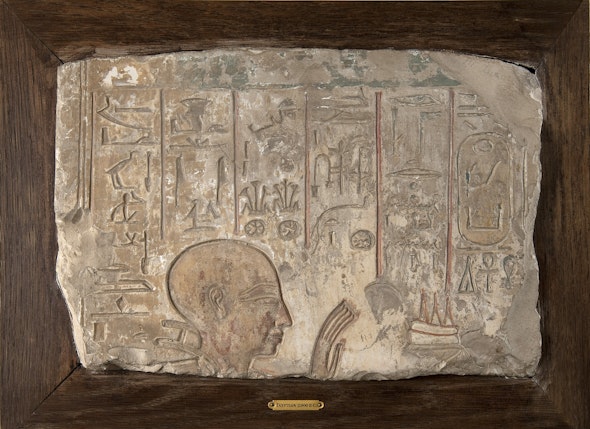

Egyptian. Relief from the Tomb of Khay (detail), 1279–1213 BCE. A107. Public Domain.

Egyptomania and the Barnes Collection

By Carl Walsh, Postdoctoral Research Fellow

September 2020

While Albert Barnes is well known for his passion for modern painting, he also had an interest in collecting art from various ancient cultures. This is evident in the Bronze and Iron Age Egyptian objects nestled among the gallery ensembles. The history of these objects not only helps us understand Dr. Barnes’s breadth as a collector but also offers a fascinating glimpse into the Egyptomania—a captivation with Pharaonic Egypt—that gripped North America and Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Figure 1: This songbook cover illustrates the clear interest in Egypt, both as a subject and as an influence in art deco styles, in the 1920s.

Dr. Barnes and Egypt in Paris

Dr. Barnes’s interest in acquiring Egyptian objects seems to have started in the early 1920s, as he began frequenting Paris in search of artworks for his growing collection. At this time, Paris was the center of the art world, with artists and dealers traveling from all over the globe to take part in the contemporary art scene. But in addition to its draw for the avant-garde, Paris was also becoming the epicenter of the market for antiquities. In the early 1900s, ancient Egyptian artworks were increasingly popular across the Western world, triggered by the sensational discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb by the Egyptologist Howard Carter on November 26, 1922. While Carter excavated the tomb, the Times (London) and other newspapers provided eagerly anticipated updates, captivating the public with the fabulous objects brought to light.¹

“Tutmania” had an enormous impact on Western popular culture. Egyptian revival influenced the art deco movement, flooding the major cities of Europe and North America with images of Egypt, from the pages of Vogue to soap advertisements (Figure 1) as well as decorative arts, architecture, and even everyday objects like pencil cases and pocketknives (Figure 2a–d).² These adaptations brought Egypt into modern art culture, where it became synonymous with luxury, opulence, and the exotic. Museums such as the British Museum in London, the Louvre in Paris, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York saw huge interest in developing their Egyptian collections to cater to the public’s hunger for all things Egypt.

Egypt on the Art Market

When Dr. Barnes traveled to Paris in the early 1920s, he entered this frenzied atmosphere of Egyptomania, making it no coincidence that he himself became interested in Egypt. Working with the famous art dealer Paul Guillaume, he began hunting for Egyptian artworks in the Parisian galleries.

This hunt was not an easy one. While Egyptian objects had once proliferated in the Parisian art market—the result of collecting, looting, and excavation in Egypt since the 16th century—the flow of new objects was being stemmed. This was largely due to the surge of nationalism in Egypt following its independence from Britain in 1922, and a renewed interest by Egyptians in preserving their cultural heritage. The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb—nine months after independence—was a political and cultural flashpoint, with Egyptians demanding that the tomb’s contents stay in Egypt. Subsequently, the Egyptian Antiquities Service tightened laws about the removal of objects, effectively ending the centuries-old exploitation of Egypt’s cultural heritage by European collectors and excavators.³ By the time Dr. Barnes and Guillaume were attempting to track down Egyptian objects, the competition with other private collectors and museums was fierce, as demand for Egyptian artworks far outstripped their availability.

Replicas and Forgeries

The ravenous consumption of Egyptian artworks also led to the development of a highly lucrative business in casts, replicas, and forgeries. Workshops in Upper Egypt, particularly around Luxor and Gurna, had been producing forgeries for some time, but in the early 20th century, other workshops appeared in Europe.⁴ Highly convincing fakes began to proliferate in Western art markets and find their way into Parisian galleries. In addition to forgeries, a number of casts and replicas were made by Egyptologists and artisans. These copies were produced to help expand museum and private collections and to be sold as merchandise, and were never intended to masquerade as ancient works.⁵ Forgeries, on the other hand, were designed to deceive buyers and sell for high prices on the art market.

Replicas and forgeries were produced and circulated at the same time. Museums and private collectors were of course interested in works of high art—statuary, relief sculpture, tomb paintings, painted papyri, architectural features, coffins, bandaged mummies, metal statuettes, and jewelry. As such, replica and forgery workshops focused on these forms, especially stone reliefs and statuary. But even simple objects such as seals and clay figurines were forged. Skilled artisans made these replicas and forgeries, modeled after real examples from collections, and they were highly convincing. In fact, they often fooled prominent Egyptologists, who would both purchase these pieces for museums and provide authenticity certificates for them to dealers. The extent of forgery making is difficult to gauge, but the period between the 1920s and ’30s was particularly active, and the rooting out of fakes became quite a heated topic for museums and Egyptologists. Dr. Barnes was certainly looking to acquire authentic works, but since neither he nor Guillaume were Egyptologists, they were not qualified to judge the pieces they acquired. Instead they relied on certificates of authenticity, which in themselves were not reliable.

The Barnes Objects

In this climate of Egyptomania and forgery making, Dr. Barnes purchased most of his Egyptian objects from Parisian galleries, between the dates of 1921 and 1939, through at least three dealers—possibly more. The objects were representative of the types of artworks most desired by collectors at the time: bronze, faience, glass, and stone statues and statuettes; stone reliefs; and a small number of miscellaneous artworks such as bone clappers, a coffin fragment, and a stone cosmetic dish. While at least three dealers are directly involved, the receipts and records in the Barnes archives do not always specify which objects were bought from whom, and in some cases, information comes from ancillary mentions of purchases by Dr. Barnes in his letters, or even in other correspondence after his death in 1951. As such, the list of dealers involved is still a work in progress.

Acquisition and Dealers

The bulk of Dr. Barnes’s Egyptian objects appear to have been purchased in Paris from a Greek dealer named George Manolakos. Mention of this transaction appears in correspondence between Dr. Barnes and Guillaume, as well as a financial document that notes a large purchase from this dealer in 1923.⁶ In January 1924, Dr. Barnes elaborated further on this purchase in a letter to the philosopher and his personal friend John Dewey, stating that he had bought a “lot of loot. . . . But best of all I found an old Greek, on the brink of the grave, who had the best collection extant of small figures and bas-reliefs—marble, stone, bronze, terra cotta, etc.—from ancient Greece and Egypt in their best periods (400–3000 BC). I got about forty pieces in which puts another unique note in our resources.”⁷ On January 24, 1924, Dr. Barnes also wrote to Guillaume, stating: “I saw the collection of ancient Greek and Egyptian figures at the University Museum in Philadelphia and they are inferior to those I bought at Manolakos. I wish you would see him and if he has any more small important Greek and Egyptian pieces, buy them as cheaply as you can by offering a reduction on the total amount of what the number of pieces amount to.”

Unfortunately, Guillaume had no luck in finding more Egyptian objects from Manolakos. The Barnes archives contain no information about how Manolakos purchased his objects or where they came from, making it difficult to ascertain their deeper history. However, two of the objects likely purchased from Manolakos were documented in other sources and can be traced back to collectors who had visited Egypt.

Figure 3: Relief of the Vizier Khay, New Kingdom. A107

The first of these is a relief of Khay, a vizier (the head of the Egyptian state bureaucracy) who served under the New Kingdom pharaoh Ramses II (Figure 3). Khay is depicted in several reliefs and documents from Egypt, and this relief provides his name and titles—vizier and mayor of the city of Thebes. This fragment almost certainly came from Khay’s tomb, which was found in 2013 by Laurent Bavay and Dimitri Laboury.⁸ However, this fragment was originally purchased in Luxor in 1895 by Lord William Amherst, whose friend and colleague, the Egyptologist Percy Newberry, published a short translation of the text in 1905.⁹ How this fragment came to be found in Luxor, before the tomb’s discovery, is unknown, but perhaps it had been removed in antiquity or by 19th-century looters.

After Lord Amherst’s death, his collection was auctioned in London at Sotheby’s in 1921, though not before the entire collection was catalogued by Howard Carter, who would go on to find Tutankhamun’s tomb the following year.¹⁰ Who bought the fragment at the auction is unclear, but it seems likely that Manolakos purchased it at some point before 1923 when it was subsequently purchased by Dr. Barnes.

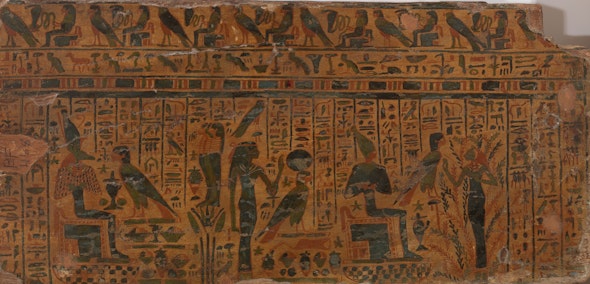

Figure 4: Coffin fragment of Tantwenemiherti, New Kingdom. BF468

The other Manolakos object with a documented history is the coffin fragment of Tantwenemiherti (Figure 4), a singer in the temple of Amun at Karnak, which dates to the late New Kingdom. This fragment matches similar fragments in the Grenoble Museum (Grenoble, France), which bear the woman’s name and titles and are clearly related in terms of their style and decorative program. Records at the museum state that the fragments were originally found near the Theban Necropolis in Egypt in 1842 by the French amateur Egyptologist and collector Count Louis de Saint-Ferriol, who added them to his private collection. After his death, they were donated by his son to the Grenoble Museum in 1916.

It is unclear if the Barnes fragment was part of this group and, if so, how it came to be separated from the fragments donated to the Grenoble Museum. It seems to have found its way onto the art market and was possibly purchased by Manolakos and then by Dr. Barnes in 1923.

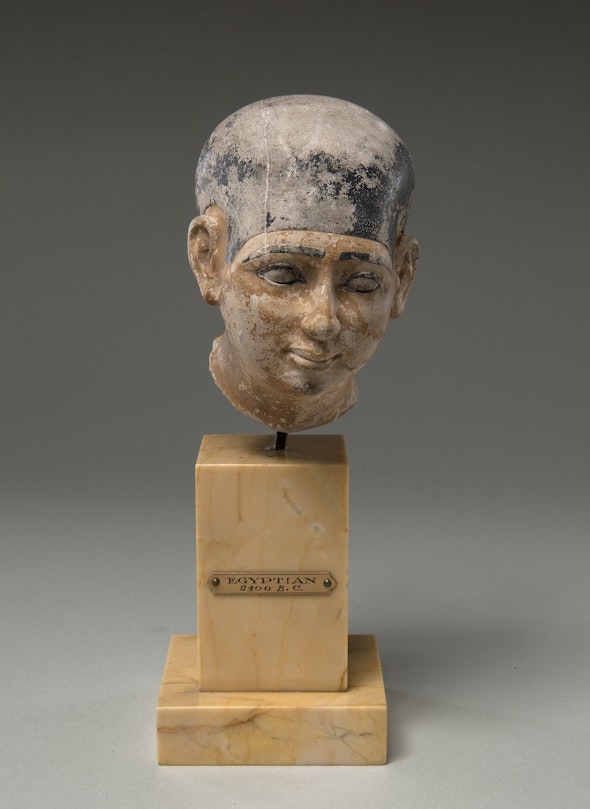

Figure 5: Head from the statue of a man, Old Kingdom (likely modern production). A409

Dr. Barnes was also contacted directly by Parisian dealers looking to sell Egyptian works. Two statue heads were purchased from Ersnt Ascher, a dealer famous for his African art collection and his personal friendship with Pablo Picasso. The first of these heads is documented in an invoice from Ascher dated May 31, 1935, along with a note of authenticity stating it had originally been part of the collection of Giovani Dattari in Cairo, and that it was dated to the sixth dynasty of the Old Kingdom by Jean Capart, head of the Egyptian department of the Brussels Museum.¹¹ Despite this note of authenticity, this head is likely a well-made forgery, as it has a number of unusual aspects for a statue of an Egyptian man, such as the yellowish skin and the gap between the ear and hairline (Figure 5). This is an example of how skillfully made these forgeries could be and how they deceived even respected Egyptologists at the time.

Figure 6: Head from a statue of a priest, Late Period/Ptolemaic Period. A431

The second head, a black diorite head of a priest, dates stylistically to the Late Period or early Ptolemaic Period (Figure 6). Currently this head is not on view; the gallery in Merion where it used to be displayed, known as the Dutch Room, was deinstalled in the mid-1990s to allow for an elevator that improved accessibility in the building.¹² The head was purchased from Ascher at an unknown date; the only mention in the archives comes from a 1960 letter from Egyptologist Bernard Bothmer of the Brooklyn Museum to the then director of the Barnes, Violette de Mazia.¹³

Figure 7a: Head of a man, likely a 20th-century production. 01.04.64

Figure 7b: Relief plaque of a man and a woman, unknown date. 01.04.53

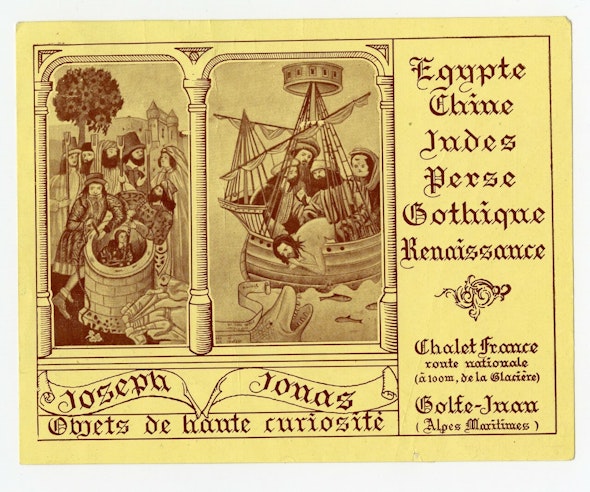

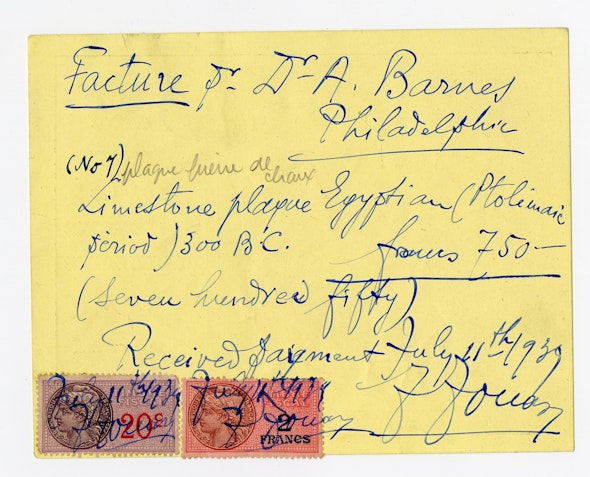

The last confirmed dealer involved with the Barnes’s Egyptian collection is quite mysterious. Two objects, a black stone statue head stylistically dating to the New Kingdom and a high relief plaque of uncertain date and origin, were purchased on July 11, 1939, from a dealer named Joseph Jonas in Golfe-Juan, France (Figure 7). The head is listed with other objects from Corfu, Laos, and Siam bought by Dr. Barnes in a two-part invoice written on the back of flyers for Jonas’s gallery. It is noted simply as a black stone head from Egypt dating to 500 BC.¹⁴ The second part of the invoice notes an Egyptian limestone plaque dated to 300 BC. The noting of a date for both pieces is unusual, especially as both dates are incorrect based on their style. No documentation appears to have accompanied them, making it unclear where these dates came from. The lack of documentation and information about Joseph Jonas makes the origin of these pieces difficult to ascertain; the marked-up flyers are the only source of information (Figure 8).

Why did Dr. Barnes purchase objects from this dealer? This is an intriguing question, because the statue head is almost certainly a forgery, given its crude manufacture and the clear signs it was carved as a broken fragment rather than part of a full statue. The plaque may also be of modern production. Further delving into the archives will hopefully shed more light on Dr. Barnes’s relationship with this dealer.

Figure 8. Invoice. Joseph Jonas, 1939. Financial Records, Barnes Foundation Archives, Philadelphia, PA.

This brief sojourn through the histories of select Egyptian objects in the Barnes collection gives a fascinating glimpse into the consumption of Egyptian art during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Some of these objects, like Khay’s relief and the coffin of Tantwenemiherti, are legacies of the deep colonial exploitation of Egypt under the Ottoman and then British empires. Others, such as the forged statue heads, are modern products of the wave of Egyptomania that passed through Europe and North America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This mixture of modern and ancient material presents interwoven stories of the changing roles and meanings of Egyptian art to audiences across time, from the Bronze Age to the modern day. As I delve further into my research on the history of these objects, more stories will undoubtedly come to light and provide new insights into how we can view these objects in the collection.

Endnotes

¹ The Times had an exclusive deal with Lord Carnarvon, who financed the search and excavation of the tomb, to supply the world press with information and photographs of the tomb. The latter were taken by the archaeological photographer and Egyptologist Harry Burton, who was part of Carter’s team. These images played a key role in the public’s interest in the tomb and are widely seen as some of history’s most iconic archaeological photographs. Burton’s original negatives are housed in the Griffiths Institute at Oxford University. The images were colorized by Dynamichrome in 2015 on behalf of SC Exhibitions and the Griffiths Institute and can be viewed here.

² For a good overview of the Egyptomania of the 1920s, see Bob Brier, Egyptomania: Our Three Thousand Year Obsession with the Land of the Pharaohs (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2013).

³ Alice Stevenson, “A Golden Age? (1922–1939): Collecting in the Shadow of Tutankhamun,” in Scattered Finds, Archaeology, Egyptology and Museums (UCL Press, 2019), 145–80.

⁴ For a good overview of the forgery industry of Egyptian art, see Jean-Jacques Fiechter, Egyptian Fakes: Masterpieces That Duped the Art World and the Experts Who Uncovered Them (Paris: Flammarion, 2009).

⁵ Stevenson, “A Golden Age? (1922–1939): Collecting in the Shadow of Tutankhamun.”

⁶ See Barnes Archive letters.

⁷ See Barnes Archive letter.

⁸ Anne-Laure Mignot, “Pyramid of the Vizier Khay,” Reflections, The University of Liège Website that makes Knowledge Accessible, 2013, http://www.reflexions.uliege.be/cms/c_346462/en/the-pyramid-of-vizier-khay?part=1.

⁹ Percy Newberry, “Extracts from My Notebooks (VIII),” Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology 27 (1905): 101–5.

¹⁰ Howard Carter, Catalogue of the Amherst Collection of Egyptian and Oriental Antiquities Which Will Be Sold by Auction by Messrs. Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge (London: Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge, 1921).

¹¹ See Barnes Archive letter.

¹² For a reconstruction of the Dutch Room, see Martha Lucy, The Order of Things (Philadelphia: The Barnes Foundation, 2015).

¹³ In his letter, Bothmer states that on a recent visit to the Barnes collection he recognized the statue head from a letter and photo Ascher had sent to him some years earlier in an attempt to sell it to the Brooklyn Museum. Narrowing the timeframe of Dr. Barnes’s purchase from Ascher may be possible through finding Ascher’s letter in the Brooklyn Museum archives, which I hope to do. See Barnes Archive letters between Bernard V. Bothmer and Violette de Mazia dated to May 19 and May 20, 1960.

¹⁴ See Barnes Foundation Financial Record.